Since the recent US release of the documentary, The Drop Box, the adoption community has been buzzing about its mischaracterization of the actual conditions in South Korea for unwed mothers and their children. Focus on the Family is sponsoring the limited American theatre release. Allegedly aiming to aid the “most vulnerable members of society,” The Drop Box positions itself as the fail-safe option to prevent children from life roaming the streets of South Korea. Pastor Lee (who maintains the drop box) and the filmmakers reinforce an outdated Christian American trope concerning orphans and children of unwed mothers.

The South Korean baby box is out of step with UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, who have called for the end of this outdated practice.[1] Committee member Maria Herczog notes: “These boxes violate children’s rights and also the rights of parents to get help from the state to raise their families.” Specifically, as noted by The Guardian, “baby hatches violate key parts of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) which says children must be able to identify their parents and even if separated from them the state has a ‘duty to respect the child’s right to maintain personal relations with his or her parent’.” In her paper, “Anonymous Relinquishment and Baby-Boxes: Life-Saving Mechanisms or a Violation of Human Rights?,” Claire Fenton-Glynn finds: “[T]here is a need to reassess the way in which society deals with the issue of child abandonment, placing a greater emphasis on the rights of the child, and achieving a real balance between these and the rights of the mother.”

The South Korean baby box is out of step with UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, who have called for the end of this outdated practice.[1] Committee member Maria Herczog notes: “These boxes violate children’s rights and also the rights of parents to get help from the state to raise their families.” Specifically, as noted by The Guardian, “baby hatches violate key parts of the Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) which says children must be able to identify their parents and even if separated from them the state has a ‘duty to respect the child’s right to maintain personal relations with his or her parent’.” In her paper, “Anonymous Relinquishment and Baby-Boxes: Life-Saving Mechanisms or a Violation of Human Rights?,” Claire Fenton-Glynn finds: “[T]here is a need to reassess the way in which society deals with the issue of child abandonment, placing a greater emphasis on the rights of the child, and achieving a real balance between these and the rights of the mother.”

In her article on the baby box and Pastor Lee, Stephanie MacDonald reports: “The children will most likely live at orphanages until they turn 18 or 19. They cannot be adopted internationally because they haven’t been formally relinquished and Pastor Lee said it is not common for them to be adopted in South Korea.” To this end there is not a guarantee the child will become registered which is critical for the child to legally exist. This is not to say that registration of an abandoned child cannot occur under Korean law. Jane Jeong Trenka points out the existing Family Registration Law’s Article 52 (Abandoned Children) was used to falsely register adoptees to enable their international adoptions.

Furthermore, you also have to wonder who is actually abandoning the children. To assume that only biological parents are the ones giving up the child would ignore decades long practices of family members and acquaintances that have relinquished children without the biological parents’ consent. This has been widely documented through personal narratives within the Korean adoption community as well as in the international adoption community more broadly. Arguably, the baby box sets up a system that will continue a legacy of falsified international adoptions and what David Smolin calls, child laundering – the misuse of current international adoption system to illegally remove children from birth parents and “use the official processes of the adoption and legal systems to ‘launder’ them as ‘legally’ adopted children.” To this end, Shannon Heit asks:

Over the past 60 years, Korea has sent over 200,000 children for adoption, and many of our birth records, like mine, were falsified or altered. Because of this, the success rate for birth family searches is a mere 2.7 percent. Is Korea going to repeat this record of human rights violations or work to ensure that this never happens again? If the intention of those arguing to revise the Special Adoption Law is truly in “the best interest of the child,” shouldn’t they be listening to the voices of adoptees?

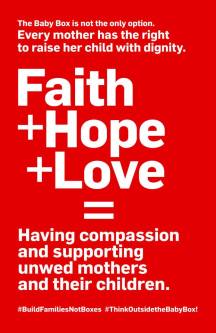

To read more from S hannon Heit about the baby box, check out: “Why I am an adoptee who is against the baby box.” And yet she is not alone in advocating against the baby box as a viable option for child abandonment. During the Los Angeles screenings of the film, Adoptee Solidarity Korea – Los Angeles is hosting a #ThinkOutsideTheBabyBox teach-in. The featured images in this post are from their teach-in materials.

hannon Heit about the baby box, check out: “Why I am an adoptee who is against the baby box.” And yet she is not alone in advocating against the baby box as a viable option for child abandonment. During the Los Angeles screenings of the film, Adoptee Solidarity Korea – Los Angeles is hosting a #ThinkOutsideTheBabyBox teach-in. The featured images in this post are from their teach-in materials.

Adoption should not be the first option nor should abandonment. As I have written about before, adoption is a reproductive justice issue. We should be advocating for women’s rights to parent in South Korea and around the world. This means learning more about the work of organizations like KUMFA (Korean Unwed Mothers’ Families Association and their allies, including Adoptee Solidarity Korea and TRACK (Truth and Reconciliation for the Adoption Community in Korea). Currently, the South Korean government’s rate of support per month, per child, is as follows:

- Family group home facility: 1,070,000 won

- Child welfare facility (orphanage): 1,050,000 won

- Foster care: 250,000 won

- Domestic adoptive parents: 150,000 won (unconditional)

- Single parents, including unwed and divorced parents: 70,000 won (only after proving they fall under the poverty line)

Why are we inhibiting South Korean women’s right to parent? Why are individuals advocating abandonment over family preservation in their support for the baby box? And finally, what does it mean that supporters are complicit in creating a new generation who lacks access to correct information concerning their biological families?

Ethical adoption practices are needed if adoption remains an alternative to motherhood. At the same time, we should be supporting family preservation. Adoption cannot serve as the only social welfare safety net for low-income families or single parents. We need to work to dismantle what I call the transnational adoption industrial complex (TAIC) – a neo-colonial, multi-million dollar global industry that commodifies children’s bodies. The TAIC encompasses how the Korean social welfare state, the orphanage, adoption agencies, and American immigration legislation facilitate the development of transnational adoption between the two nations.[2]

[1] Please note that South Korea is not the only nation who still maintains baby boxes. In fact, the State of Indiana is currently deciding on whether or not it too should introduce this method of child abandonment.

[2] My examination of the transnational adoption industrial complex will appear in forthcoming issue of Journal of Korean Studies. I will share the link once it is available online.